Is California's internal coronavirus model showing a mid-to-late May peak realistic?

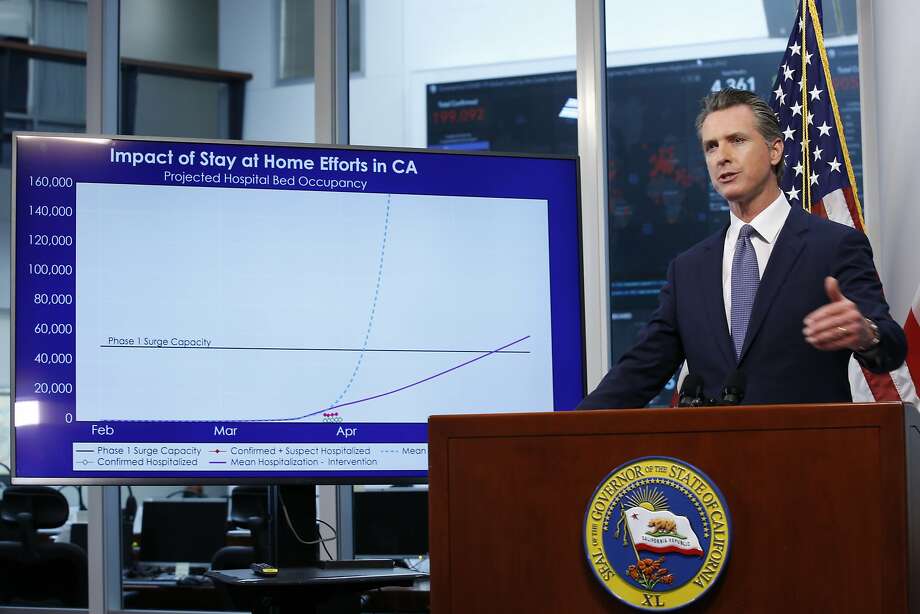

During a news conference last week, California Governor Gavin Newsom and Health and Human Services Secretary Dr. Mark Ghaly told the state's residents that internal modeling suggests California will hit its "peak" on the curve of the coronavirus pandemic sometime in mid-to-late May, despite widespread social distancing measures.

"We know that the bending or flattening of the curve means two things," Ghaly said. "It means our peak comes down, but it also means it goes further out. We move that lower and further out. So our thinking around May, and late May in particular, means it follows this idea of flattening. It's not just a reduction down, it's moving it out."

This projection is not in line with other models for California, including the highly influential IHME model used by policymakers at the federal level.

The IHME model — one that also takes into account a state's social distancing efforts — projects that California's hospitals will hit peak resource use on April 13, and the state's number of daily deaths will peak on Wednesday.

In addition, top-line figures for Kaiser Permanente's internal model reviewed by SFGATE shows that the managed care consortium expects peak resource use sometime in late April. That timeline is a week or two behind the IHME projections, but almost a full month ahead of the California internal projections.

So why the discrepancy?

SFGATE reached out to California's Office of Emergency Services for information on the science behind the state's internal model but did not receive a response.

Dr. George Rutherford, an epidemiologist at UCSF, said the state model uses two other models — the University of Pennsylvania CHIME model and Stanford University's model — to make its own projections. While Rutherford is not entirely sure how the state weights each model, he believes that reliance on the CHIME model could lead to overstating the spread of the outbreak.

"The CHIME model is exquisitely sensitive to case doubling over time, which is purely a function of testing," Rutherford said of the interactive model. "I put some numbers in with a case doubling of three days as opposed four days, and there was a huge, huge difference. Doubling times are not what you want to hang your hat on since they're a function of testing."

California's testing situation has been far from ideal, as early lags and a massive backlog of unreturned tests have distorted the state's case doubling time figures.

In addition to the emphasis on case doubling time, others have questioned the infection numbers the internal state model uses. John Ioannidis, a professor of medicine, epidemiology and population health at Stanford University, told POLITICO last week he believes the state model is using an infection rate as high as 80 percent, an "unrealistic" worst-case scenario "based on early observations elsewhere that have since been walked back."

It's unclear if the California model is extrapolating based on New York's outbreak, but Ioannidis believes that would be ill-advised since "the vast majority of the world is not as dense and intermingling."

While Newsom has stated in recent days that the state's model shows a flattened curve, other models have shown the same flattening without pushing the peak of the curve into May. For example, the IHME model has downgraded the number of expected California hospital beds needed and daily deaths on multiple occasions in recent weeks while still projecting the same mid-April peak.

"Models are all based on what data feeds into it," said Dr. Alexei Wagner, the assistant director of Adult Emergency Medicine at Stanford University's School of Medicine. "And so if you look like last week compared to this week [in the IHME model], the California numbers are much flatter, the peaks are lower. And I think there is a sense that the work that we've done for social distancing, social isolation is definitely starting to flatten the curve."

So what's the best data to feed into models that would most accurately project both the height and expected timeline of California's peak?

Rutherford believes the answer is hospitalization data, and stated that UCSF models are predicated on these figures since they are "hard numbers."

The hospitalization data for the Bay Area has been flat over the month of April. Rutherford believes the Bay Area will be peaking at the beginning of this week, a tad earlier than the statewide IHME model projection.

“The IHME model is a blended model, it reflects what's going on in the Bay Area, Los Angeles, the Central Valley and it's not pulled apart," he said. "My best guess — and these are just guesses now — early [this] week is our peak, followed by Los Angeles a week later. Los Angeles cases are way higher, like ten-fold higher than San Francisco ... It went up very rapidly in Southern California largely driven by L.A. a week after statewide shelter in place, but this was a rapid rise that was not seen in the Bay Area since we went into shelter in place three days earlier.”

If Rutherford, the IHME modelers and Kaiser Permanente are correct in projecting that California will peak and start "moving down the curve" earlier than the state's internal model predicts, the timeline for reopening could possibly be moved up.

During a Friday night appearance on CNN's "Anderson Cooper 360," Newsom stated he would follow the actual trends the state witnesses in real time over the next few weeks when making his decision.

"If over the course of the next few weeks we see this modest growth begin to bend in a different direction, then I will be in a position, based upon the expertise of our health professionals and based upon where this virus is, based on more expansive community surveillance — meaning testing — make that determination," he said.

The governor also cautioned against "running the 90-yard dash against this virus" and "getting ahead of ourselves" when it comes to discussions of reopening, a sentiment shared by health experts.

"The worry is that if, if anything changes or people start going out because the media is saying, 'Oh, it's just not as bad,' then will we see another spike or an uptick later?" Wagner stated. "Or is this going to come back in the fall? And that's why everybody's kind of like a little bit freaked out. But I do think we'll start, we won't have the significant surge that we were planning last month, but we are just very aware and vigilant that we will likely see a bump at our numbers as more and more patients get the virus, but we will have capacity to care for them."

Rutherford agrees, and says he understands why California's internal model was geared towards a potential worst-case scenario.

"If you want to miss, you want to miss high," he said. "If you miss low, the consequences are unbelievable. It doesn't bother me at all the numbers are higher, in an abundance of caution. You saw what happened in Italy and New York. I can guess that the state models are sensitive to things that are difficult to measure, but I’m not the one having to procure a bunch of hospital beds."

More Information

Comments

Post a Comment